In taking things apart in their entirety, Paula Louw leaves

very little unsaid. The works of art, these objects of meticulous, excruciating

detail, seem to embody their own meaning. It is the act of witnessing the end

result of her process that I find startling and compelling. The meaning of

Paula’s work lies inextricably linked to the experience of being fascinated by

it, caught up in the act of witnessing it in all its complexity.

When looking at her work, I find myself drawn into it;

compelled by it. In addition, the nature of the experience is fascination. I

cannot help but be aware of the huge amount of work—intensive, physical

labour—that has gone into the work. Her labour is an act of revelation, of

simultaneously discovering and imbuing meaning. This is the nature of creating

art from existing objects; the result refers to both existing (historic)

meanings, and yet-to-be-discovered, new meanings.

Art, here, is the practice of bestowing upon an ordinary

thing the gift of beauty. Of turning it into a source of admiration; of

reviving our fascination for a dead object. Art, here, gives new life. The

dismantled pieces are now objects of veneration, ready to be regarded in new

and different ways.

As we look at the work now, we are confronted with something

new and profoundly different from that thing we previously presumed to know and

understand. We experience the sensation of being drawn into the moment—an act

of meditation, perhaps; a freeze-frame opportunity that allows us to

concentrate on the object and observe its difference from the thing it once

was, the thing, which it resembles now in only abstract ways, requiring complex

intellectual processes of which we are not even aware. It is an act of

contemplation resulting from the studiousness of the project; the opportunity

to witness a moment in time and— thanks to the physical form of her

work—witness this moment from multiple angles.

Continuing this metaphor, it is apt to point out that this

is precisely what Paula does with her deconstructed/reconstructed artworks: She

stops time in order to get to (or expose) the meaning embedded in banal,

everyday, ordinary objects. I experience this as a bit of a trick, though,

because when she takes them apart and transforms them, they cease to be banal.

I say “trick” in the sense of being and an act of magic, rather than an

illusion. She transforms objects into artworks that are fascinating in and of them.

So, whereas this piano might previously have been fascinating because of what

could be done with it (producing music when played by an artist), now it is an

object of fascination in its own right. It has attained multiple new meanings,

repeatedly refigured by everyone who views it. Transformed in this way, it

necessarily refers to its former life (as a piano), but draws us into an

altogether different discourse around its present state. Now we look at the

piano in a reverential way, as if it were a disembodied, spectral version of

its former self.

Or perhaps, rather than seeing the ghost (of a piano), we

are seeing its corpse…

Perhaps it is because there is so much to look at. Minutiae

and intricacies revealed within the objects she dismantles seem to suggest the

presence of the sublime in even the most banal objects. If you look around this

gallery, it is nothing more than a vexingly shaped room with vast walls and a

magnificent approach. However, insert Paula has dismantled piano, and suddenly

this space becomes a surgery for the practice of visual dissection. In

addition, the piano is suddenly not merely a dysfunctional instrument that has

been put out to pasture, but is now hallowed; revered. As watchful eyes gaze

upon it, its nature is transformed, and as light falls upon it, the shadows on

the walls become objects too; and sources of intrigue. Paula says that in

pulling apart old things she is breaking apart an established order, but I

think she is also paying tribute to that order, she is reminding us (and no

doubt herself in the process) of the value of that order. After all, in order

for the piano to produce music the way it does, it must necessarily be put

together in a certain way. By taking it apart, she reminds us of the genius of

human creativity, just as dissecting a human body reveals the brilliance of

Nature. To come up with a piano is to have produced something magical. There is

magic in order. Yet, when she restages the piano in a new and unexpected way,

we are forced to consider the piano in all its parts, a bit like the way in

which a person is considered differently after they are dead. The way you look

at the re-imagined piano might echo the experience of reading or hearing an

obituary. You will grapple with the piano in profound ways that might not have

been possible—or permissible—when the piano was “alive”. In its original form

the piano perhaps loses meaning, fades into the realm of the ordinary, gathers

dust, and is potentially forgotten. Paula has bestowed new life on this object,

and this act of resurrection fascinates and enthrals.

Her work may suggest to us something like a disembowelment

or autopsy, but I find Paula’s work life affirming, a reminder of the human

potential to create, to imagine, and re-imagine. In addition, by displaying the

many parts or components of an act of creation, her work becomes a meditation

on creative process itself. “Don’t just see a piano,” this piece seems to be

saying.

Look at the piano; stare at it and be reminded of the human

potential for fascination. It is an invigorating study; captivating and pulsing

with life, even as it invites us to contemplate the afterlife of an ordinary

object.

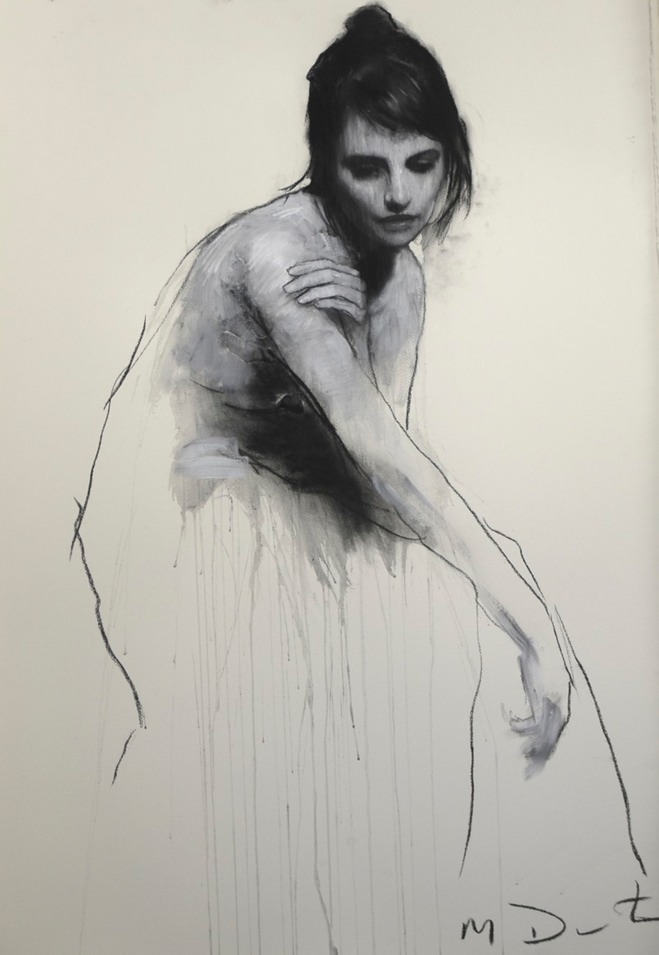

“Much of my work is expressive so there is always something

new for the viewer to notice and discover, even after long inspection. My work

is an ongoing process of self-challenge and evolution, I do not like to get

stuck on a recipe. I want to give people the opportunity to enjoy and interpret

my work largely for themselves.”

“Much of my work is expressive so there is always something

new for the viewer to notice and discover, even after long inspection. My work

is an ongoing process of self-challenge and evolution, I do not like to get

stuck on a recipe. I want to give people the opportunity to enjoy and interpret

my work largely for themselves.”